The simpler times

In the Spring of 1972, a twenty-three-year-old Greek lands in Athens, running away from responsibilities and chaos created on the other side of the world. He hopes to get himself work and make enough cash to return and set things straight. Fifty years later, he declares to his youngest daughter that there’s only one thing he regrets in life, “Getting used to money earned easily”.

There are quite a few important things I was puzzled with as a little person growing up. Did Jesus Christ talk with the twelve gods of Olympus and take over as the one God? Does that mean the twelve gods have retired? Where in the sky does he live? How can I make sure I never cross the Bermuda Triangle nor find myself in quicksand?

Equally intriguing was the behaviour of adults around me. I found some of them alluring while others seemed like a fraud. My father, though, a mystery: a complicated man.

A friend asked me to write about growing up in the nineties, but looking back, I feel there’s not much significance to it. For the majority of my lifetime, I experienced what we'd call a stereotypical family. Adults going to work, coming back, having dinner, meeting with friends, spending weekend nights at the bouzoukia, parking the kids with the grandparents during the summer holidays, buying a couple of cars, and owning at least one proper family house. The plethora of money during that era made this lifestyle very much the norm. People had both the time and the mindset to focus on the mundane

I feel both lucky and guilty for having had a good life due to a financial bubble. The days before doomsday were quite beautiful. During the summer of 2004, I was bedridden with mono while watching the Olympics; apparently, I had kissed someone I shouldn’t have. For my fifteen-year-old self, making out with a boy and watching Greece win the Eurocup felt like flying too close to the sun. The 2008 crisis brought about the 'money-police' rhetoric and media messages drumming in the notion that 'we all ate the money together.' “I was young; I didn’t know,” I'll tell my cousin in Australia when she insists that all Greeks are to blame for their demise. The kids didn’t know, truly. However, looking back, most of it began to make sense.

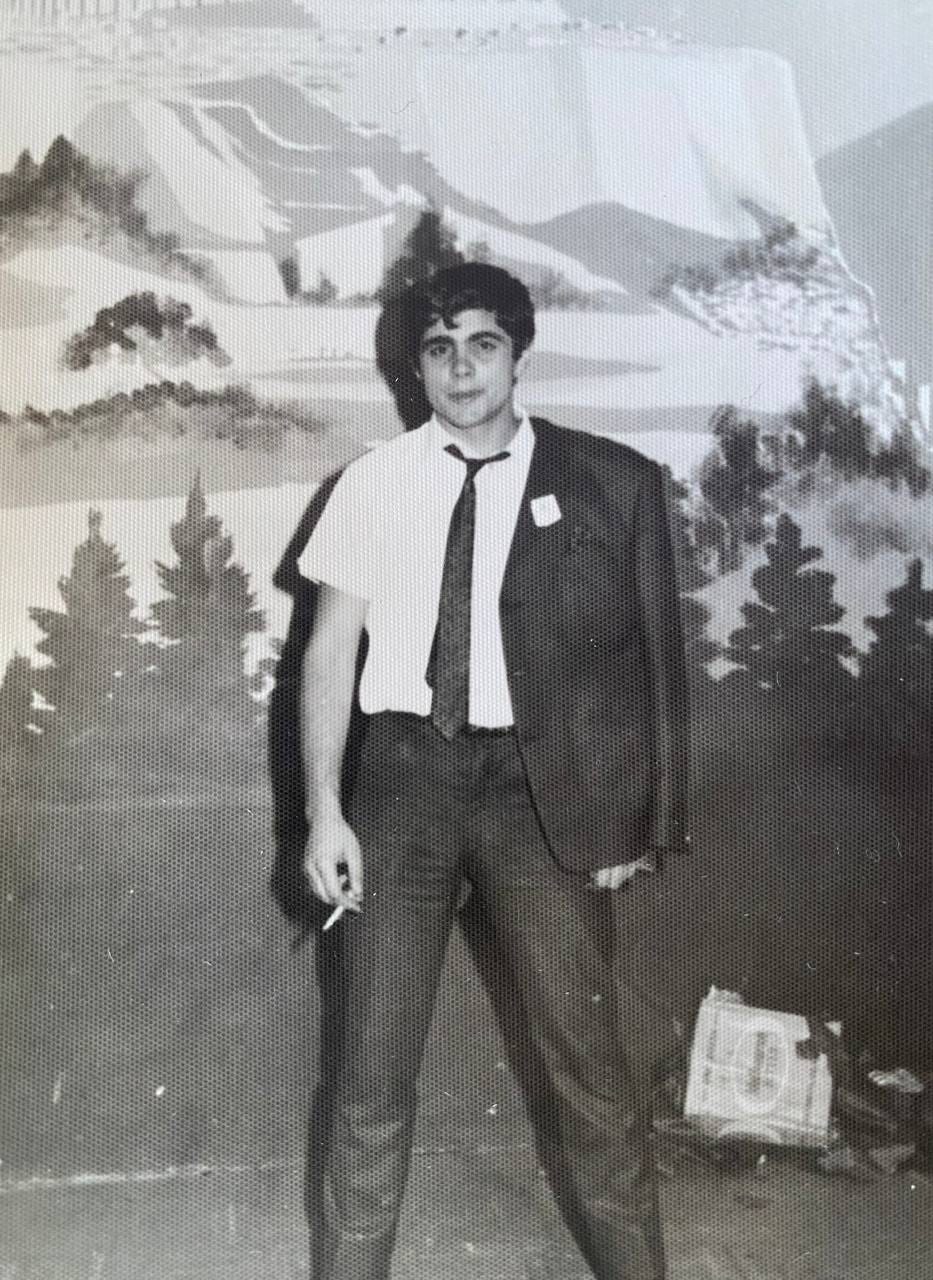

The man who reached Athens in the Spring of 1972 was my father. The need to make ends meet prevented him from getting involved in the resistance against the junta. Instead, he operated with a free-spirited, 'home-is-everywhere' mindset. At the age of sixteen, he left Greece for Australia, alone, with scarcely any farewells or concerns from his parents. In rural Greece, children were seen as labor hands; the more you had, the better your chances of survival. However, during his teenage years, he was quite the rebel. The village was too confining for his character, and his family thought it best to send him away. He often says that this never bothered him; it was simply how people behaved at the time. He felt he had no choice but to look forward.

Like his older siblings, Australia could have been his opportunity to build a good life. Alas, accepting a stable life requires a certain mental state, and he struggled to find peace with what most considered 'normal'. Instead, he delved into gambling and the underworld that came with it. He made money, though not through conventional means, and ended up getting a beautiful Polish girl pregnant. He didn’t want to be a father, and while no one pressured him to take an active role, he still distanced himself from the whole situation. That his son is now a part of our lives feels nothing short of a miracle, deserving its own story.

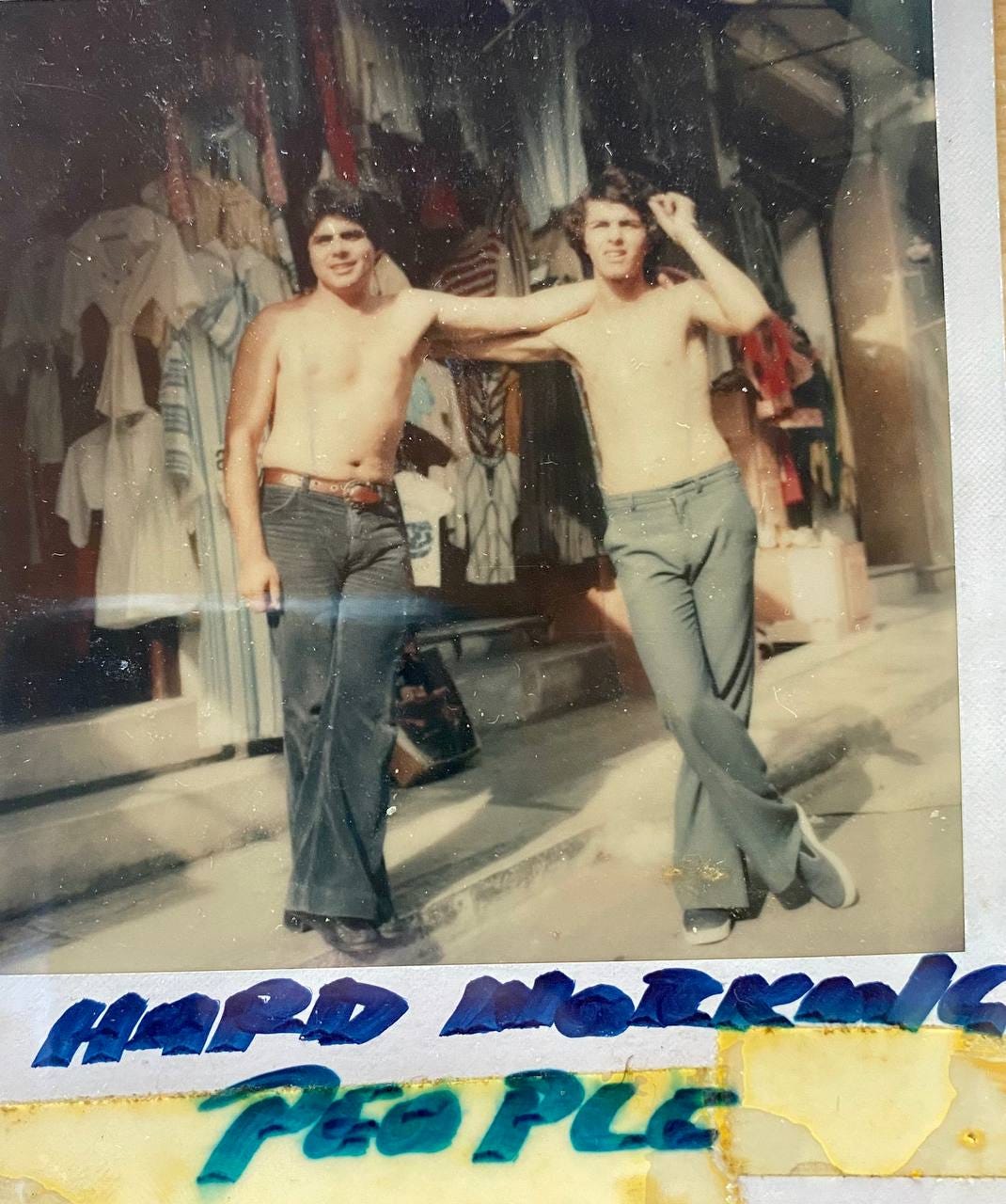

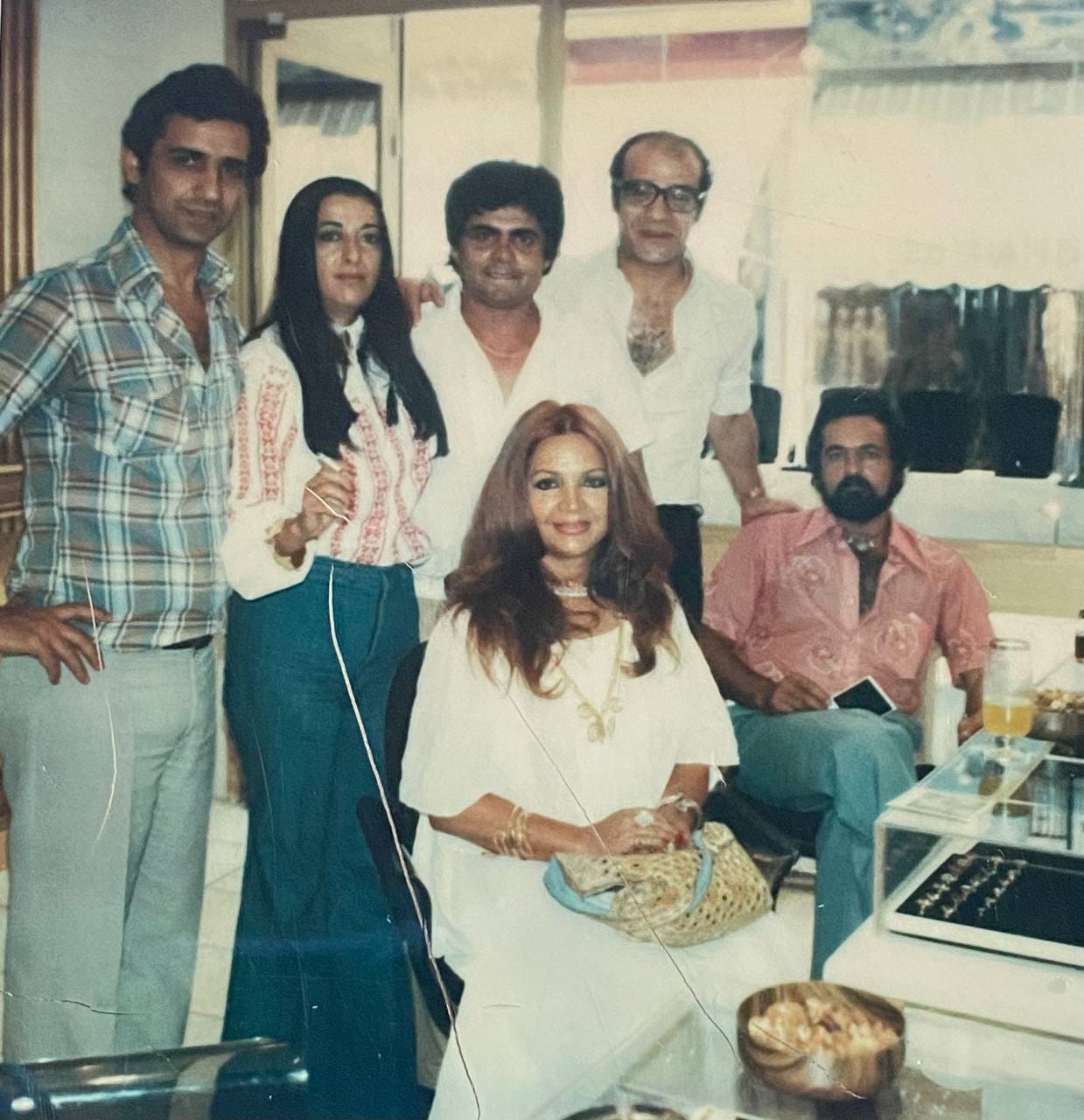

After escaping from the land down under, he spent his days selling jewellery and goods on Pandrosou Street. It's that quaint street filled with shops next to Monastiraki, sitting in the shadow of the Acropolis. It was the most popular tourist marketplace in the 70s and 80s, though its allure faded in the following years. My father and his fellow sellers could earn up to seven thousand drachmas a day, a tidy sum back then. Working six months out of the year, they'd spend their free time travelling to South America, hitchhiking across Europe, or wintering in a Northern European home with a foreign woman they'd met under the Greek sun. Some would return for the following season, while others settled in distant lands, having discovered better opportunities. My dad returned for several more summers, meeting others like himself. Men who grew up with similar hardships, determined never to experience them again. These were men who never pledged allegiance to any system, politician, or ideology; they simply looked ahead, doing what was best for themselves and their loved ones.

In the time between, he spent his days in London, at a girl's house. He said he loved her a lot, but left for a reason he can't recall. There's a photo of him with long hair, sitting at a podium, addressing a young crowd in Hyde Park. I've asked him several times about the subject of that speech. “I don’t know… some hippie nonsense! Freedom, democracy, all that,” he'd say. He often followed up with stories, likely a blend of fiction and reality. He spoke of how easy it was to find fellow travelers. He reminisced about days in the south of France, dining at restaurants and dashing out before the bill came due, and about his time in Munich with a German girl who observed his comings and goings for almost four years

After the fall of the junta, he returned to Pandrossou, now in a revitalised Greece teeming with tourists. That summer, he and his peers encountered more renowned foreign visitors, rick folks, and beautiful blonde women seeking a Greek fling. They enjoyed showing foreigners a good time while they sold gold in US dollars, profited from foreign currency exchange, evaded taxes, and bribed policemen to look the other way. The money they earned was reinvested in various, likely illicit, ventures to guarantee even greater profits.

Whenever I press my father about these stories, I always inquire about the politicians' roles. To my surprise, he often says that, initially, they were largely in the dark, mostly “begging” for votes and campaign funds. Only in the late 1980s and 1990s did politicians begin to exploit the hand that fed them. In the early 1980s, many of these men posed as self-made, respectable figures in society. They wore fine clothes, lived in elegant homes, and often married attractive young women. By making solid investments in real estate, funds, and improvement projects, they ensured a relatively stable future for their families.

You’d reckon this happened with us as well. To some extent, it did, but our journey was marked with ups and downs closely tied to my father's emotional state. There is this story circulating in the extended family circles that my grandmother cursed her son ‘to never be able to hold onto money in his life’ and while there might be nothing supernatural about it, the subconscious is quite powerful and one could easily tell that he didn’t do well with abundance. The first year he made his first million, he grappled with depression and irrational behaviour. He visited a shrink and after a few sessions, convinced himself that the therapist was crazier than him. That alone was enough to make him feel better. He considers this a pivotal moment. I want to believe it also explains why he decided to always spend what he was making the years that followed.

By the time I was born, it seemed he had left his old ways behind. I witnessed his highs, his lows, and the lukewarm moments in between. He was filled with nostalgia for the simpler days, the leaner years, and the time he spent in the village. He rejected the pretentious savoir-vivre of the nouveau riche, a stance that often embarrassed us and made those around him uncomfortable. Nonetheless, he could light up dinners and parties, only to become gloomy shortly afterward.

You might assume that abandoning their former habits meant that the men of his generation had shifted to legitimate endeavours. While some did transition, many merely became entangled with more influential players. 'The Crisis', as we Greeks refer to the 2009 government debt debacle, came as a shock to the nation. The average citizen, oblivious to the extent of the underlying corruption, clamoured for justice. The question on everyone's lips was, 'Where did the money go?' Subsequent investigations unearthed various major corruption schemes involving both Greeks and foreigners. Some of the individuals named in the now-public court testimonies were people with whom I had shared meals as a child. I would overhear my father in hushed conversations with friends: 'Have you heard about X? Were you aware of that?

When I asked how he felt about having worked with and been close to those individuals, he sighed, 'They didn't know when to stop, Georgie. No one can save them now.' By the time everything crumbled, he had already divorced, retired, and moved back to the village as he'd always wished. He had transferred his inheritance to his children, ensuring it was beyond the reach of banks. Once again, he found himself with nothing, free to wander, having sidestepped the dangers that ensnared some of his peers who had flown too close to the sun.

His retired life is equally chaotic. Some days, he steps into the shoes of a traditional grandfather: farming the lands, tending to animals, cultivating a garden, and distancing himself from modern life while keeping only a handful of friends near. When months pass and he realises that he’s not dead yet he’ll yearn for company, conversations about politics, a good shave and the buzz of Athens.

I might have tricked you that I was always able to experience my father as a character from a book. However, this perspective only emerged recently, after years of grappling to understand him, our relationship, and its finite possibilities. His deep-seated fears and anxieties demanded much from his children. I spent my teenage years trying to be close to him and when he was up for it it was a lot of fun, we would talk about boys and politics and laugh at everyone around us. Yet, for the most part, our shared memories are ones I've only ever discussed with my therapist and close friends. We jest amongst ourselves that our tight-knit bond stems from our parallel tales of dysfunctional families. We've dissected our fathers' manipulative tactics, their pettiness, and the gamut of emotional to physical violence. Such narratives aren't meant for those with 'standard' parental backgrounds; their gazes would cloud with fear, and understanding would remain elusive. It took me years to connect with those who had relatively joyous childhoods. Only after accepting that such upbringings exist was I able to bond. But make no mistake, every family has its shadows; the distinction lies in how they maneuver through them, and to what extent they become ensnared.

Throughout this tumultuous journey, my circle of friends, predominantly women, remained my anchor. We would call each other crying at times, ‘will things ever change’ we’d ask. There's a certain pride, not arrogant but fiercely resilient, that I hold for our journey. We had decided early on that we’d make sure to overcome, to tame the beasts. For all of us it included the following steps: going no contact, falling back to acceptance and pain then putting a foot down, building our own life, speaking back at them and hanging up the phone when necessary, with no remorse or guilt. When we realised nothing will change for us until we do. For those of us who kept those paternal ties, it’s been anything but straightforward. But for most of us the storm has passed, and we stand, rooted, undaunted by what may come.

“You only still talk to him because you didn’t go through what we did” my step-brother whispered one balmy summer evening in 2017, a summer that had been filled already with its own share of difficulties. His words, though carrying the weight of our shared history, were tinged with bitterness, the kind that only stems from a place of deep-seated hurt. The temptation to measure pain, to claim the heaviest burden, it’s a peculiar side effect of fractured homes. After all, what was he truly trying to convey? That I was spared? Perhaps. But more than that, it echoed a more profound pain, a need to be acknowledged. I explained to him what I keep saying to everyone who asks. In the grand tapestry of existence, there’s a moment, a poignant frame, where you see the ones you once held dear cross the river of eternity. Coins in hand, their silhouettes fading, and the realisation that life's grievances remain tethered to the shore. It’s a reckoning of sorts. And I aim to stand at that juncture, not with unhealed wounds or unresolved bitterness, but with understanding. To see him, not just as fragments - the adventurer, the wanderer, the melancholic spirit, the father figure, but as an entirety. Neither saint nor sinner, but an intricate interweaving of complexities. The thought comforted me, that when that boat sails, I'd have my peace, acknowledging that he journeyed through life with the best he knew, and perhaps, the best his courage allowed him.

Looking back, I've come to understand my father in layers, each one revealing more of his complexities. I’ve recognized that he offered what he could, and what he couldn’t, I've already mourned. This understanding has been instrumental in shaping me for the world beyond. I’m eternally grateful, because scared people try to scare you all the time in adult life - insecure bosses, immature boyfriends, older people who think age is a legitimate factor of intimidation. I remind myself that I was able to stand up to my fathers angry frown a child filled with guilt and the internal agony that he might burst at any minute and If I was able to do that I believe I’ll do more than fine in this life. They can turn their threats elsewhere and they better do it quick.

This summer, I see him as much as I can, in doses that my psyche can tolerate. Now at seventy-six, he's grown introspective, looking back at earlier years, questioning his past decisions. "Did I make mistakes when you were younger?" he'll often ponder. "That's water under the bridge," I'd assure him, knowing that revisiting the past won’t change much for us now. In an attempt to redirect, I might say, "I’m thinking of switching jobs, but it won't be remote. What do you think?" He'll muse, "It's a reputable company, that's good. We can come visit you." But then he’d pause, adding, “You've always been one to crave freedom. Don’t cage yourself.” In those moments, it feels like he's reflecting on his own life more than mine.

He watched a film on Patagonia. "I should go," he said, "before I die." He eyed me, a twinkle of mischief surfacing. "You should come. You know, if I don’t return, someone would need to bring back my body." I laughed, “Oh yes, of course!” We delved into the morbid and the whimsical by asking if he’s ever thought about his funeral plans. “Only a wooden cross, no marble please... cremate me perhaps, funerals are costly and I don’t want the church making any money out of me”. I nodded, expressing the hope that we might dance around this conversation for years to come, the end always a distant horizon.

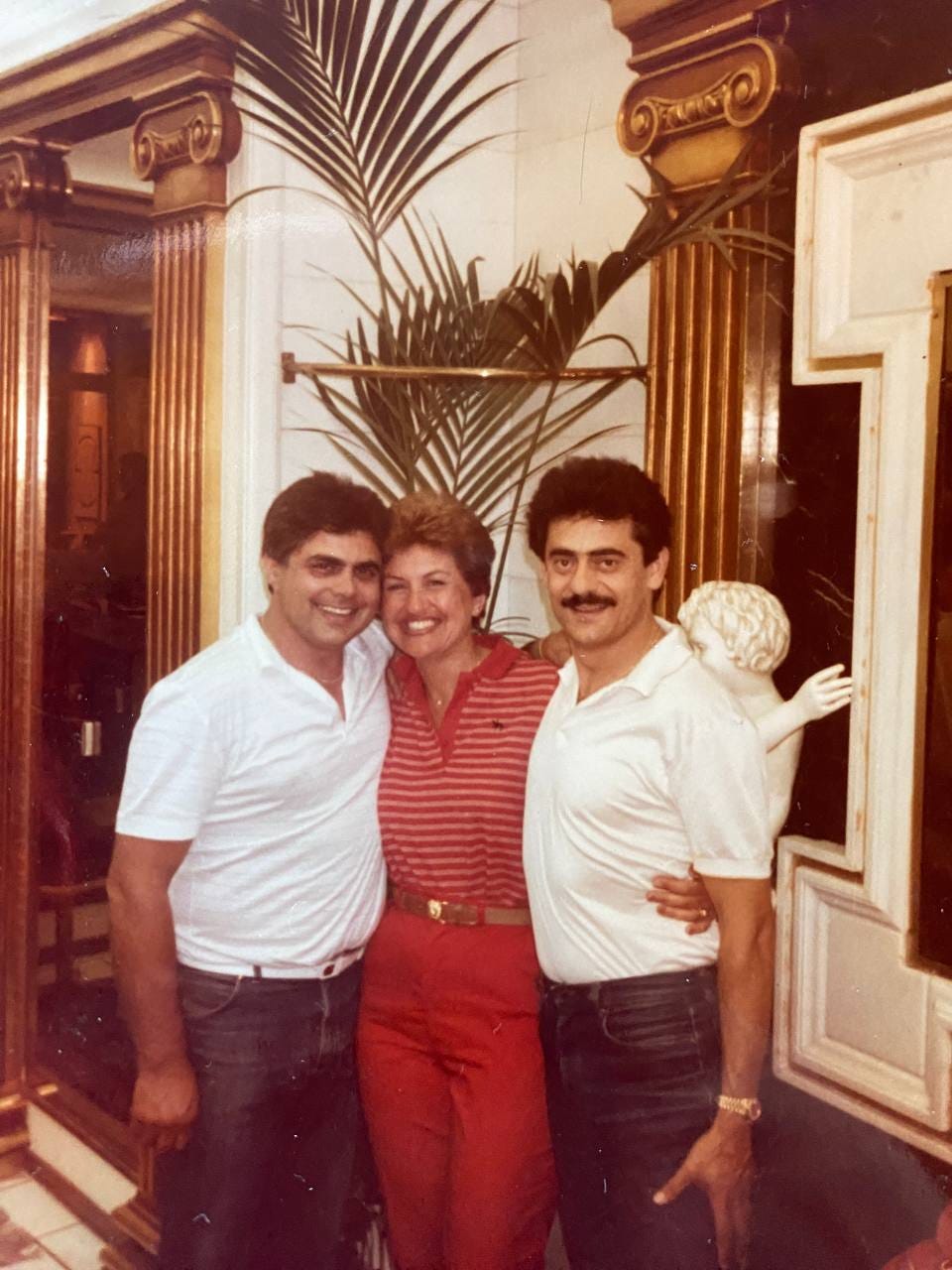

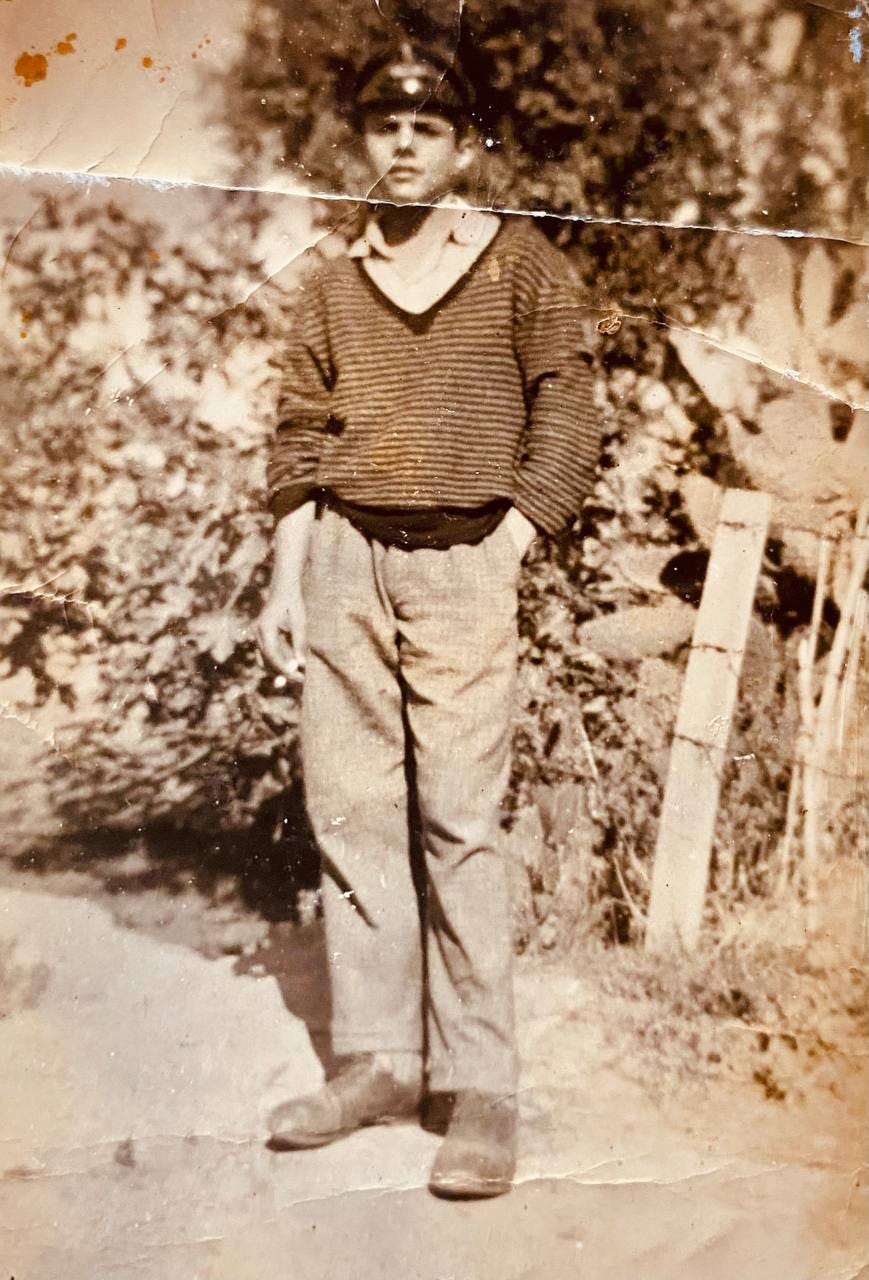

p.s. Some more pics of simpler times

Amazing, insightful, heartwarming, clever. Full of wisdom, full of awareness. May your sharing help all those having dealt or are dealing with the complexity of the complexed. May you continue enlightening us in service to all in this human experience. I am in awe of who you have become and of all your gifts and talents. I love you 🙏🙏🙏🥰👩❤️💋👩💕you shine 🧚🏻♀️🌈🍭🌻🌷⭐️Be blessed, your mom 💕