Byzantine ruins

A travel story

Two Spaniards and a Greek walk into a bar.

“What are you having?” asks the bartender.

“A beer! A local one if you have” says the Madrileño.

“A wine! Fruity but on the acid side please, if the grapes grew in volcanic soil I’d appreciate” says the Canario.

“What’s your name?” asks the Greek.

Dani, Pablo and myself wake up in the city of Kalamata on an early September morning of 2022. We exchange the usual morning glances, fight for bathroom time, complain about who snored, who slept or didn’t sleep well, ramble on which of our Bumble matches replied and whether we’ll have enough time for breakfast before we need to set sail for a trip to the past.

We are not setting sail per se but setting sail has the right emotional weight here so I’ll stick with it. To the past I’ll add, because I was 33 years old then and the last time I had made that trip was when I was probably no older than 12. To the past, because we are going to the side of Greece that birthed and fostered Leonidas, Byzantine jewels and the relationship of Kazantzakis and Zorbas.

The boys were happy because it’s an extremely rocky land, boulders to climb or dream of climbing. “You guys are sick” I repeat multiple times per day in every sight of a rock and the excited claim “Look at that! Climbable!”

First stop is the small beach of Kytries. The water here provides a certain level of enhanced buoyancy and we wanted to see how it feels to be the woman who floated for six hours near the Barcelona coast, found in perfect condition in the middle of the night. We concluded that it was probably the boobs that helped her stay afloat for that long and no man would ever have a good fortune like that.

After getting a good sun roast and two freddo espressos each in our bellies - Greece’s modern gift to civilisation, we decide that the best course of action is visiting yet another beach near Kardamyli where the home of Patrick Leigh Fermor was for many years. The beach is called Foneas, meaning “the killer” and is hidden in one of the steep turns right outside the village. It’s almost six in the afternoon so the sun is gentler. The same way it’s gentler in September, with fewer people bathing under it. The boys climb the beach rocks while locals stare, puzzled. I pretend I don’t know them… “these foreigners…crazy people” I mumble.

We reach Aeropoli at night, starving. I get excited at the sight of the almost unwelcoming stone houses. Aeropoli is one of those towns where time paused at its peak time of beauty. I remember that if we walk a little and follow the buzz we’ll end up to a plaza with more stone houses and bougainvilleas, jasmines and all sorts of greenery appropriate to a Mediterranean little town. It seems to thrive without any intervention, putting our efforts to re-create such scenery in our city balconies to absolute shame.

Finding a place to eat was tricky given it was dinner time for everyone but I was certain there is always space. There was no way we wouldn’t find it. Greek taverna owners and waiters feel extremely bad when they don’t have a corner to offer you. They’ll ask their bosses, they’ll put you in the kitchen, get one more table outside illegally, winking at you, agreeing that if anyone asks anything we will figure it out. It’s very few times they’ll give up. Closing hours, peak tourist seasons, when despair from overwork has overtaken them, maybe. They feel it’s their task for you to be fed and eat “their” food because who knows in what situation you might find yourself or at what sketchy less tasty place you walk in.

We find our table. Water, bread and olive oil is placed in front of us as a mandatory start before any questions are asked. A sweaty waiter comes, letting a big sigh, leaning in, putting his best face and starting with a “Hello! How are we doing tonight?”. I reply with “Kalispera” so he knows I’m Greek in case he’d like to speak it and although pleased, he declares that he will continue in English so our guests understand - I had little doubt. He starts listing every food item on the menu like a radio announcement, an overwhelming list.

“Patates!” shouts D and the waiter smiles listening to a foreigner speaking Greek.

“Mia?” he asks, gesturing his finger to make sure they know that “mia” means one.

We nod happily, order some more classics and find that the waiter already knows what “vegan” means and he enthusiastically offers lent dishes to P. The waiter leaves and I take the opportunity to stress how in Greece we don’t have to tag options as vegan because we don’t put meat in everything and lent is still very much important and part of the food culture and the boys roll eyes. “Yes yes, we know…”.

My lecture on Greek culinary history stretches to history about the place, the architecture, why is this town important and all sorts of legends that might not be very accurate but add to the flare and make for a great story. I realise that I sound like a snob, trying way too hard to make my friends feel how I want them to feel, knowing that although charisma and great storytelling helps, most times your context needs to align with the listeners preferences and the preferences of my friends at the time have nothing to do with war, independence, sacrifice for land and culture and that’s fine. Their disinterest helps me relax a bit as I get disproportionally passionate about such matters. What’s more noteworthy is how I’m considered a proud, history obsessed Greek by my foreign friends and at the same time a foreign-lover, globalist by my compatriot ones.

“You sound Spanish!” my greek family in Australia will tell me on our annual calls in case I already don’t have enough guilt for abandoning our country.

I understand now that this disconnect is only a result of my way of communicating which often demands from the other to see the different way as if believing in something very strongly might end up strangulating their thoughts and perceptions of the world.

“Everyone speaks Greek right?” my kid nephew asked once and I had to explain about the Babel state humanity lives and how it make things a bit difficult but also so much more beautiful. “What are you saying to the little one?? The greek language is the best” his grandma shouts from the kitchen. I sigh and pretend I didn’t hear that except when I have enough energy or piled up anger, I’ll start a debate until the end with anyone mouthing such ridiculous claims.

Some call this being a contrarian and although I would love to be one I don’t have the courage to insist on contrarian beliefs with such aggressiveness. I’ll start with “I understand where you’re coming from but what would you say if….” whereas I wish I was more trusting on people to tap into their own capacity for self-questioning. Even better, I hope I’ll have less of a need to crack open ones head and force them into different ways of thinking. It’s alienating and none of my friends should go through doubting their own thinking so much as I do with mine. In any case, this part of myself is still fermenting. I doubt I’ll ever be zero combative in conversation but highly considering being mindful about what I’m so passionate about in the first place. I always ask, what am I really angry about here?

In case you forgot, we are still in our first night at Aeropoli. While enjoying the feeling of a day well spent, our eyes fall into a group of people in their early twenties. It’s a table of six, four boys and two girls, all extremely beautiful, radiating. We comment on the odds of finding so much beauty stemming from youth in one place. Their beauty is filling us with a sense of admiration and sadness. Yes, we are still young but what we’re seeing is the exact definition of the beauty of youth. What Greeks and Romans had in mind when drawing nymphs and sculpting statues. We know that our lamenting for lost youth is a universal experience and we remind ourselves that probably a bunch of middle aged folks in another table are watching us, thinking, “If only I were thirty again, I don’t need to be less than thirty - too innocent, just thirty would do. ”

The next day we get caught up in heavy rain which felt alleviative. We buy cheap masks from the local kiosk, bathe alone at the port of Oitylo. We see many of the modern Mediterranean invaders, the silvery pufferfish. We talk about the migrating fish species sneaking their way to the Suez Canal, global warming, the enemies of humanity. What are we going to do? Watching the sunset over the Messenian gulf for starters, swimming until it’s too dark and we can’t see the poisonous pufferfish any more.

As much as I’m enjoying this, even more when I see my friends happy, what I’m hankering for is seeing the town of Monemvasia, located on a tied island off the east coast of the Peloponnese.

I asked chatGPT to describe Monemvasia the way different writers I admire would, it kind of failed. I prompted it “yeah, can you do it more poetically”. It failed again. I wanted something more mystical, something more soul wrecking, something dark to align with the idea we have about the Byzantine times. Finally, I type, “what if Edgar Allan Poe visited Monemvasia. What would he write about the city?”

Amidst the craggy cliffs and tempestuous waves, there stands a city forgotten by time, a ghostly apparition of a bygone era, Monemvasia. Its ancient walls, cloaked in mist, loom like the shadow of death over the desolate streets below, where the only sound is the mournful cry of the seagull. Here, in this city of the dead, one can feel the chill of despair that clings to every stone, the melancholy that lingers in the air like a haunting melody. The memories of the past, so vivid and alive, seem to have seeped into the very fabric of the city, leaving behind a pallor of sorrow and loss that permeates everything. And yet, amidst the ruins and the decay, there is a strange and terrible beauty, a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur that can only be found in the darkest of places. Monemvasia, the city of the dead, may be a place of sorrow, but it is also a place of wonder, a place where the soul can find refuge from the sorrows of the world and be at one with the shadows.

Dear reader, the description is quite accurate, emotionally wise at least. The machine of “if” and “elses” vomited a spirited passage for Monemvasia, that old city on top of what people know as Monemvasia today. The lower part of the city, the one next to the sea, is very much alive. The past is ricking up in its’ walls but the tourist shops, the lively bars and the taverns keep it somehow less ghostly during the extended summer months. The old city however, the one found at the top of a rock, requiring a steep walk round and round not for the faint of heart, nor the ones afraid of heights, is very close to what Edgar Allan Poe would have written for Monemvasia if he had visited.

One must see that place both day and night. If you have to choose go during the night, right during the sunset, grab a sleeping bag and sleep amongst the ruins. Under a full moon if you prefer a lot of light, under a new moon if star gazing is your thing.

Before I deduce Monemvasia to a poetic, mystical place, I tried writing something more historic like. Since I’m quite emotional about the place I struggle to glue sentences together without sounding like Wikipedia or bore you to death so I simplified things in my mind with the following keywords:

Midieval-fortress, old church of the 12th century, Malvasia wine, Hagia Sophia of Monemvasia, public baths, the view of the Myrtoan sea, ships coming in, the light of the moon, the feeling that you are between two worlds, venetian ships going to the west, pirates trying but not daring, the jewel of the Byzantine empire, old olive tree, Romans, Franks and Arabs.

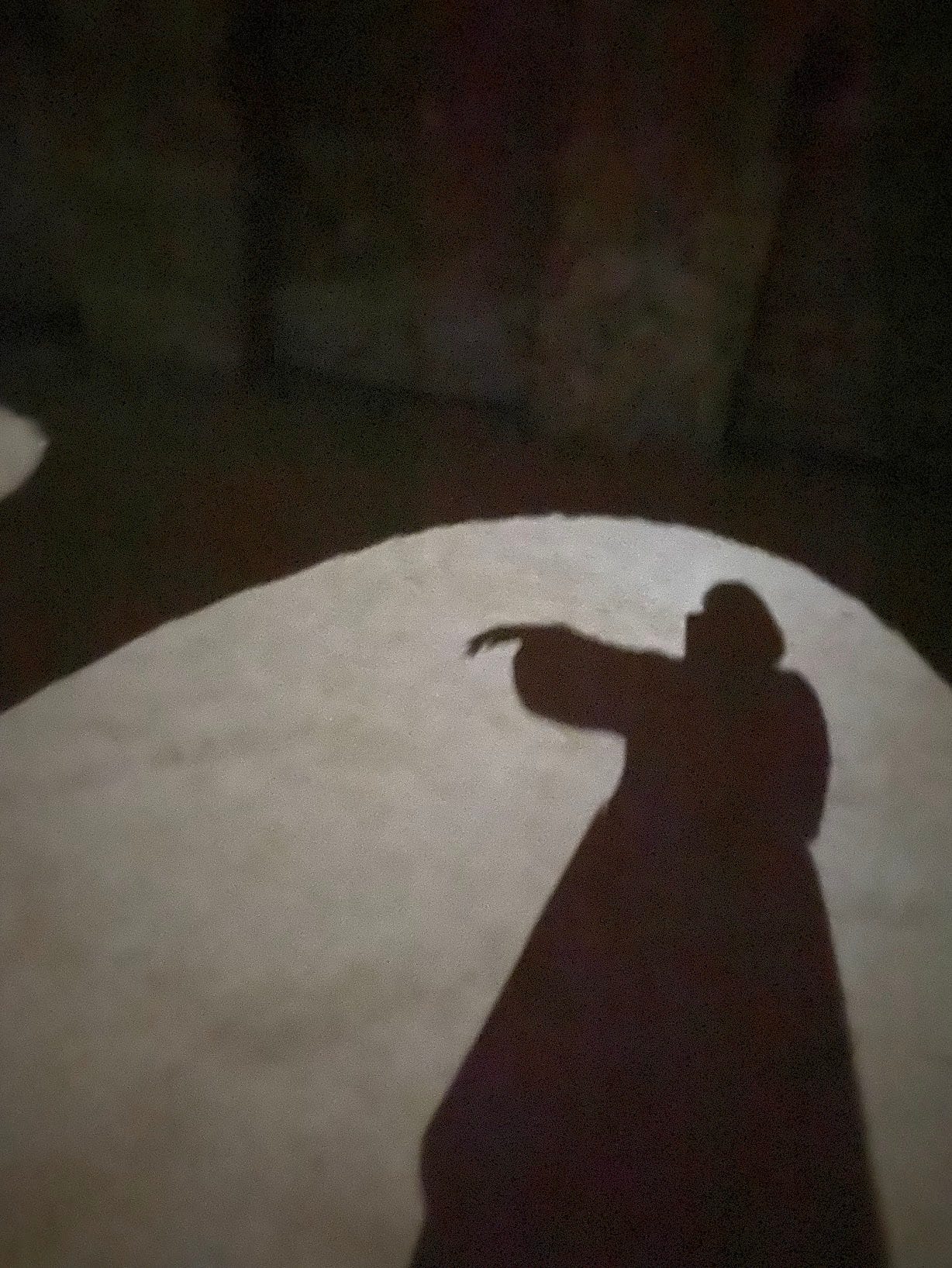

During our nights there we spent our time in that place and all I could think of, is what would a local woman of the 12th century say, seeing me taking photographs playing with the shadows of the ruins at their house, making baroque hands with my reflection. How amazing it is to have a testament of the past, the feeling that you are looking at the same view as them, touching the same stones that had their original Malvasia wine spilled on them during a feast. That if a ghost appears before you, you will tell them to run away because the Franks are about to sack the city and by the way, we call you “Byzantines” now.

What I strive for while being at this place is to lather up my insides with the idea that there is a repeating cycle we all abide to. Our preoccupation with the now in the grand scheme of things is what should keep us going. I enter the 12th century church knowing that people did the same gesture a thousand years ago and they have no idea how long any of this will last, no idea that this will be a museum piece for fools like me. This thought transforms to immense respect for those people of the past, who lived their lives day in and out, committed mandatory daily acts of trying to live an honest and beautiful life, not knowing that the future will always look back at them and be grateful.

I always look at old portraits and art and I remind myself that whatever worry that person had at the time doesn’t matter, they are dead now, everyone around them is dead now. What’s left is a testament, art, fiction, music, science, a legacy, everything for the collective to admire. I’d like for us belonging to the current collective to understand that simply and clearly. Not because we need to make art and we need to leave a legacy - but please do that if you want, but because it’s exactly through life lived that legacy is made. The way you talk to your family, your friends, the people around you, the art you make at your room alone, the way you live your life as courageously as possible is what adds up to all the little things and makes a single piece of the world exist, until the world explodes and there’s no one to remember. One more reason to do it anyway. When people say “I want to write or sing or try for this or that but I’m afraid” “What are you afraid of?” I ask with a rhetoric tone.

Our last night at the old city of Monemvasia, I had brought my mind back to the present. We were sitting on top of ruins with my friends, discussing our plans to bring our next love of our lives here one day. How they should see what we are seeing and how great it would be to share it with them. Despite our future yearnings, we know that what we have here now is a blessing on its own and that when we do bring our future partners up here most probably our minds will wander at the time that once it was us. We will be reminded on how P kept “Not Dark yet” on repeat and the moon was reflecting at the vast sea in front of us. How we felt immensely content but also worried about what comes next, how much there’s more to see in this world, how much more the world will change during our lifetime.

The day that followed found us taking a last dip at the water, teaching P how to dive head first and struggle with the idea that there are people in this world who don’t know how to swim. We hurried to get on our way to Sparta for a photo-op with the statue of Leonidas, followed by another rocky uphill and downhill hike to see the castle and village of Mystras. At the top of Mystras, we find sitting amongst the ruined town, the Pantanassa Monastery. Still very much alive, with nuns dressed in black, sweeping the floor, watering their plants and feeding a myriam of cats, we enter it humbly with our touristy outlook, trying not to disturb on our way to the main church. One of the nuns is greeting every passerby, gesturing with her hands “Don’t be afraid!” and come in closer. She asks where we’re from. I explain that I’m Greek but those with me are Spaniards. She smiles and excitingly explain that the monastery holds very close relationships with their sisters in a monastery in Salamanca and Malaga and how they have visited one another in the past. She’s thrilled to show us around.

As much as we want to stay some more, staring at the view to the green valley in front of us, the sun has only a few hours to live for the day and we need to cross the mountain of Taygetos to get back to the city of Kalamata. Crossing it during daylight is a must and although its roads used to make me extremely sick when I was a kid, it’s a sight one can’t miss, especially nature lovers and religious climbers. Taygetos doesn’t disappoint and I’m glad to find out that curves don’t make me so sick anymore, better cars I guess, smoother driving, feeling somehow safer.

With this last mountain path, our trip is ending and each of us goes back to whatever business they had at the time. Retrospectively, I’m grateful for most of our decisions. Travelling in September, renting our own car, not having a schedule, only organising in advance the places we would sleep and above all, not hurrying to see absolutely everything. The type of trips you don’t return tired from but rather well rested, well fed, content, inspired.

Later that year, we found ourselves in a bodega on the island of Lanzarote. The sommelier assigned to guide us is an Italian woman who fell in love with the island and its wines and decided to stay. While we were trying out the Malvasia Volcanica variety I wanted to tell the story of the name of this grape and how some months ago we were at the town that birthed its trade. Fearing that I will sound like a snob once more, I kept quiet. I was content with the fact that this grape, like others, has found itself in all parts of the world and although I didn’t get to drink the Malvasia that was being sold at the port of Monemvasia, here I am, on another ocean, a 21st century Greek looking happily at what the Malvasia variety has become and feeling lucky existing amongst people making great things with it. Perhaps, I was already quite drunk.

P.S.: In this story, I’ve left out lots of beautiful sights and experiences, circumstances and lucky encounters. It was the general feeling I wanted to outline so I don’t forget. An exercise to remember why old things have such a chokehold on me and why this was important to me at the time. I haven’t done neither the place nor our trip justice but if you ever wish to take a similar route dear reader, let me know.